IN UNTIL THE END

Story by Van Hansen, as published in the Nov / Dec 2011 issue of Canadian Aviator

The “target for tonight” was proving proving to be no such thing. Inside the hut that served as the sergeants' mess, pilot Matt Kennedy's Royal Air Force (RAF) crew stared at the briefing board in disbelief. A briefing at 11:30 hours could mean only one thing. The next day, April 5, 1945 they would fly their first daylight operation (op).

RAF 205 Group operated their B-24 Liberators from Southern Italy primarily at night, unescorted, with each aircraft navigating to the target individually. Kennedy's crew was part of 40 Squadron, which together with 104 Squadron made up 236 Wing at Foggia Main.

From the other side of the airfield, B-17s of the 15th U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) flew missions against the same targets, but in formation, during the day, escorted by P-38 Lightning and P-51 Mustang fighters.

"I never liked that aircraft, because it was a bit of lumbering beast. Most of our Liberators had a faired-in nose because we didn't need a front turret at night, but George had the front guns so it was a bit heavier and slower," says Kennedy.

The ground crew was ready with the boosters. Kennedy and Engineer Dave Bremner did a cockpit check, then started No. 3 engine first, the starboard inner as it ran the hydraulics.

While the B-24 had dual flight controls, the RAF operated with only one pilot, with the engineer in the right seat. Kennedy had taught his engineer, navigator, and bomb aimer how to land.

Bomb aimer Maurice Harmes checked the racks carrying two 1,000 pound, and ten 500 pound bombs, with fuse wires in place.

The heavy bomber rumbled forward on the airfield that was built out of well-rolled local soft rock and topped with pierced steel planking. Lifting off at 13:45, and leaving the squalor of filthy Foggia behind, Kennedy executed a turn to port, heading out toward the sea. With the 15 planes from 40 Squadron, there were about 100 bombers on the op, a maximum effort for the group.

As usual, Harmes was bugging Wireless Operator Jim "Mitch" Mitchell to get some music on. Mitch tuned in to American Forces Station Bari, and Tommy Dorsey's Orchestra filled the headsets.

Some smoke flares were dropped and rear-gunner Stan Mansfield lined up his turret to measure the drift, passing the information on to navigator Cyril King.

The music stopped abruptly as Mitch was having trouble with the intercom.

Half an hour from the target, Harmes left his waist gun position and started forward on the narrow catwalk which ran over the fuselage keel beam through the bomb bay. His lifejacket snagged on a bomb rack. It inflated and trapped him there. The bomb-bay doors opened and Harmes could see all the way down. Finally the doors closed again. Mitch had been testing them. Spotting Harmes, Mitch rushed over to help.

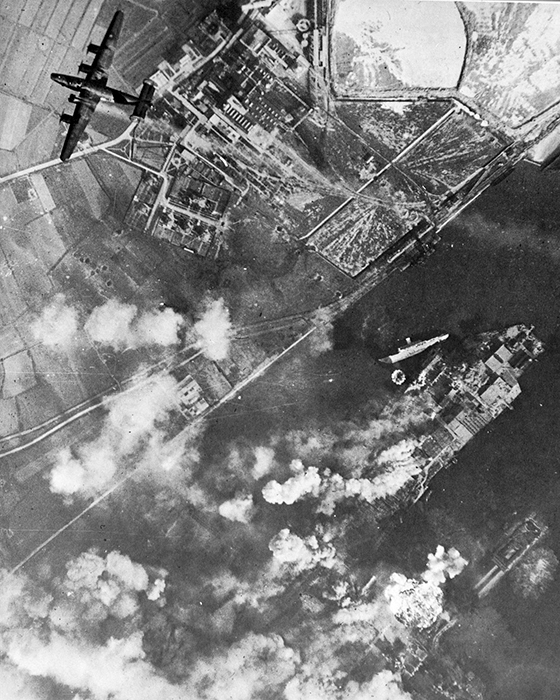

On approach to the target the crew was happy to see the USAAF P-51s providing fighter cover. Twelve anti-aircraft batteries made for medium flak, with greasy black puffs of smoke filling the air. They spotted a Liberator from another wing leaving the target below them with its port inner engine on fire. Each of the wings was assigned a different bombing height, with 236 Wing and G for George at 10,500 feet.

Over the target, Harmes was in position on his stomach peering through the bomb site. But to give direction to Kennedy with the intercom out, he would raise his right leg for turning to starboard, left for port, and both for straight and level. King stood on his navigation desk and with his hands relayed Harmes' signals to Kennedy through the astrodome.

Aiming point was the jetty and after the bombs were away Kennedy held straight and level for 30 seconds so they could take a target photo, timed for impact. Turning 180 degrees, Kennedy put them on a heading for home. The flight back was uneventful, and they landed at 1728.

At the briefing they found that their signals had worked because they had the best target photo, which was used to plot the bombing results for the squadron.

"As a crew we got very close, and we probably knew one other crew fairly well, but you really didn't want to know the rest in case they didn't come back one night," Kennedy says. "At the time I was 20 years old, and we were all about the same age.

As far as we were concerned, you never thought about the danger. In fact it was like an adventure. You always figured it was going to happen to the other guy. Now that I'm older of course I realize how stupid that was," says Kennedy.

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

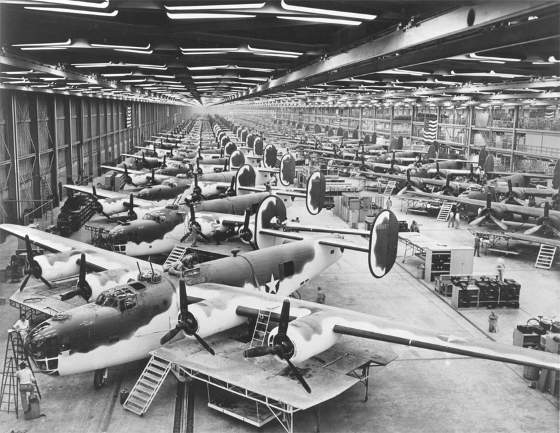

With world tensions escalating, the U.S Army Air Corps (USAAC) was looking for a second manufacturer for the Boeing B-17 bomber. Consolidated Aircraft Corporation was approached in 1938, but offered instead to develop a new, more advanced bomber. The first aircraft, XB-24, made a successful flight in December, 1939.

The B-24's "Davis wing" offered a high aspect ratio (long length of the wing compared with the chord or breadth), with greatly reduced drag over then-current designs. This gave the B-24 higher fuel efficiency and longer range. Its two adjoining bomb-bays were each as large as the B-17's single bay. New innovations included roll-up bomb bay doors and tricycle landing gear used for the first time on a large aircraft.

For all the advantages of the new design, it was less stable than the B-17 and more difficult to fly.

The only aircraft able to provide cover for convoys in the mid-Atlantic, the B-24 is credited with many U-boat kills. Other roles included reconnaissance, tanker, cargo, and personnel transport.

B-24s were built by Consolidated at plants in San Diego and Fort Worth, by Douglas at Tulsa, North American in Dallas, and Ford near Detroit.

From 1940 through September 1945 more than 19,000 were built making it the most produced heavy bomber, and most produced multi-engine aircraft to date. Of these 2,100 served with the RAF, and 1,200 with the RCAF.

In August, 1943 all five plants switched over to the B-24J, which was the variant made in the largest numbers, and which the RAF called the Liberator B.VI.

"With the Lancaster and all the British planes, they took a bomb bay, put wings and engines on it, then as an afterthought they stuck the crew positions on," says Liberator Pilot Matt Kennedy. "On the Liberator, you go up on the flight deck, there's a carpet on the floor, the seats are really nice and comfortable, and there's bulletproof steel on the back. The American design provided more crew comfort."

___

In-flight hazards both in training and then on ops, other than those presented by the enemy included several engine failures, and a lightning strike. Putting a large number of bombers over the target at one time in an attempt to overwhelm the defenses created its own problems and during ops the entire crew had to be constantly on the lookout to avoid collision or being bombed from above. "We would be flying over the target and you look up and there would be a plane above you," says Kennedy.

On the night of April 25, 1945 Kennedy's crew participated in what turned out to be the last RAF bombing op of the war, a marshalling yard near Salzburg, Germany.

On the way back from a re-supply mission to the British Army on May 7 they heard on the radio that the war in Europe was over. At that time they believed they would have to take their bombing ops to the Far East. Given the option to convert to Lancasters or transfer to 70 Squadron, staying on Liberators, the crew transferred on January 10, 1946. By the end of March they were told that 70 Squadron was being disbanded and the crews were being split up.

"This was an emotional time. We had bonded as a crew, relying on each individual to keep us all safe from harm," Kennedy says.

For a few months, Kennedy flew with East African Headquarters Communication Flight in Nairobi, Kenya flying the Hudson VI, which had been converted from bomber to transport.

At the rank of Warrant Officer, Kennedy was released from service on August 7, 1946, and said his goodbyes. After arriving home he rejoined the Edinburgh City Police, ultimately reaching the position of Acting Sergeant in the Criminal Investigation Bureau.

Kennedy got to fly again in 1955 when he was commissioned as a Flying Officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force Reserve after immigrating to Canada. On a cross-country trip from Hamilton, Ontario in a DHC-1 Chipmunk, Kennedy got too close to the American side, and was intercepted by two USAF F-86 Sabres. Coming along-side, they gave him long scrutiny, saluted, and then peeled away.

He flew about 20 hours each summer from 1955-57 until the Diefenbaker government did away with the Arrow fighter and also his flying program. Kennedy's most recent flying was in 2006, in a Stearman biplane in Palomar, California.

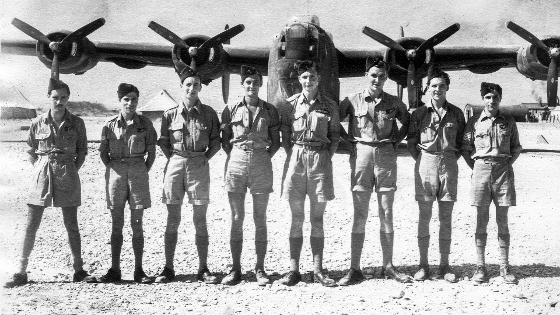

THE MAKING OF A CREW

Pilot Matt Kennedy had been a police clerk in Edinburgh, Scotland when he volunteered with the RAF.

On October 28, 1944, he reported to no. 76 Operational Training Unit (OTU) where members of the air crew trades assembled in a drill area and the order was given to crew up.

The first person to join Kennedy's crew was Jim Mitchell, wireless operator. "He was Scottish, I was glad to meet him," says Kennedy. They met another Scot, flight engineer Dave Bremner, who had been an apprentice at Leith docks in Kennedy's hometown.

The boys then got talking to bomb-aimer Maurice Harmes, the most colorful character to join the crew. Kennedy says, "Maury was a real ladies man. With slicked-back hair and sporting an Errol Flynn moustache."

Harmes asked if air gunners Stan and Charlie Mansfield could join them. The first thing that Kennedy noticed about the Mansfields, other than the fact they were identical twins, was that they were small, the ideal size for gunners.

The last one to join them at the OTU was navigator Cyril King, from Luton, outside of London. "King was a quiet, bookish type, and a real gentleman," says Kennedy. Ron Tarrant was added to the crew later as a waist gunner.

"In spite of the haphazard way crewing was done, we ended up with a happy, efficient crew who got along well with each other," says Kennedy.

__

Matt and his wife Sheila settled in the Bronte East neighbourhood of Oakville, ON and raised five children. Matt worked as a manager at the Ford Motor Company, for 35 years until his retirement.

He also volunteered for many years in various roles including Commander, Search Master, and Quartermaster at the Town of Oakville Water-Air Rescue Force a unit of the Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary.

The Kennedy's were married for 63 years, when Sheila passed away on September 10, 2016.

Matt was born on Christmas Day, and he passed away on Valentine's Day, 2017 at the age of 93.

__

Market | News | Events | Never miss a story—subscribe now to our free monthly newsletter:

Housing Horizon is your Market, Economics, and Rate Review with Q & A—don’t miss it!

Comments:

Post Your Comment: